In the late 1850s, Melbourne was one of the most prosperous cities in the world. Gold flowing from the Victorian goldfields created wealth on a scale that few cities could match. Trade boomed. The population surged. Within a few short years Melbourne had overtaken Sydney in size, confidence and economic weight, becoming the wealthiest port in the southern hemisphere.

Such fortunes rarely go unnoticed. In an age of imperial rivalry and naval power, prosperity carried with it an uncomfortable implication: it made a city a target.

To Victorian eyes, the most likely threat came from Imperial Russia. Still embittered by the bloodshed of the Crimean War, the Russian Empire was widely believed to be eager to strike at British interests wherever they were most vulnerable. A sudden raid on Melbourne — distant, lightly defended, and awash with gold — seemed not merely plausible but inevitable. Russian warships, it was feared, could slip through the Heads, sack the city, and escape with untold riches before any serious response could be mounted.

To many Victorians, the Russians were coming. It seemed only a matter of time.

Or so the Victorian Colonial Government believed.

In reality, Russia emerged from the Crimean War economically hobbled and technologically behind its European rivals. Its infrastructure was outdated, its navy overstretched, and it possessed no colonial network to sustain long-distance operations. Yet to anxious colonial minds half a world away, these strategic realities offered little comfort. The fear was not of invasion and occupation, but of a swift, humiliating blow — a lightning raid that would enrich Russia and expose the vulnerability of Britain’s far-flung empire.

That fear, however misplaced, would prove immensely productive.

A Colony Arms Itself

Concern over Melbourne’s defences was not abstract. Port Phillip Bay, for all its treacherous entrance, was largely unprotected. There were no permanent heavy batteries guarding the Heads, no coordinated minefields, and only a modest naval presence. In the event of a hostile squadron forcing its way into the Bay, there was little to stop it.

In 1856, spurred by mounting anxiety, the Victorian government established the Royal Colonial Victorian Navy, charged with the colony’s maritime defence. It marked a rare assertion of autonomy: a self-governing colony raising its own navy to protect its wealth.

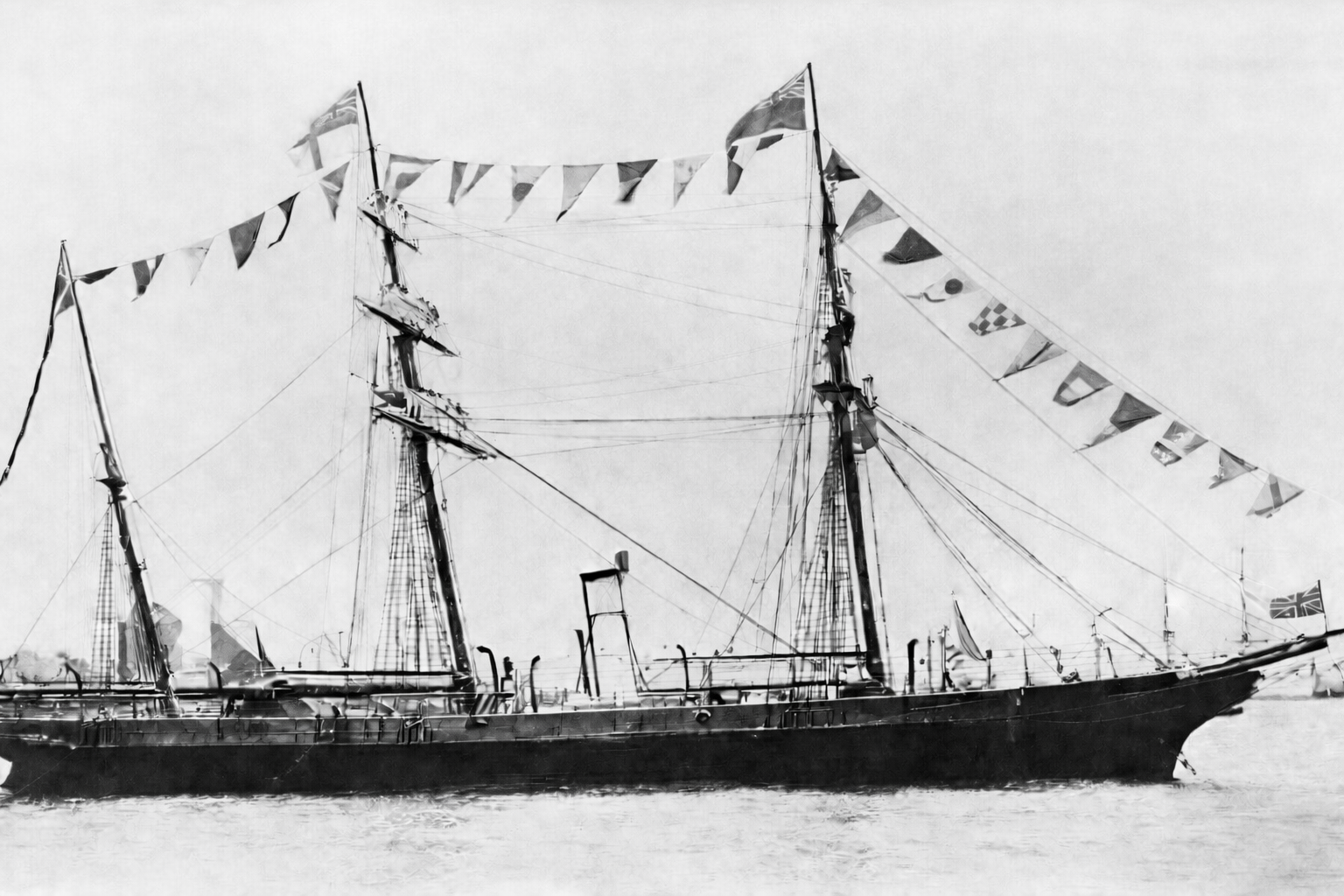

Victoria’s first warship was the steam sloop-of-war HMVS Victoria, purchased from the Limehouse dockyards in London on 31 May 1856. Designed by British naval architect Oliver Lang, she was only the second warship ordered for the Australian colonies by the British Admiralty. Crewed largely by volunteers, Victoria served in local waters and later saw active service in New Zealand during the Māori Wars.

Yet the arrival of HMVS Victoria did little to settle colonial nerves. One ship, lightly armed and thinly crewed by inexperienced volunteers, offered reassurance rather than real protection. Worse, subsequent events would highlight just how exposed Melbourne remained.

Uninvited Guests

In 1862 the Russian frigate Svetlana entered Port Phillip Bay. Her arrival was entirely peaceful and conducted with courtesy, but the visit landed like a thunderbolt. A foreign warship — from the very empire Victorians feared most — had entered Melbourne’s waters without challenge or resistance. Three years later, the Confederate raider CSS Shenandoah arrived at Williamstown, again unopposed.

Neither visit was hostile and both were legal and diplomatic. Yet together they exposed an uncomfortable truth: Port Phillip Bay could be entered at will by foreign warships. If an enemy chose to come, there was little to stop them.

The implication was unmistakable: Melbourne’s defences were not merely inadequate — they were largely theoretical.

A Ship Fit for Hell

By the late 1860s, the Victorian government concluded that symbolic measures were no longer enough. In 1867 it secured, on permanent loan, the steam-converted HMS Nelson and committed to the purchase of an armour-plated monitor or turret ship “capable of carrying 22-ton guns” from the British Admiralty. The cost was £125,000, of which £100,000 would be borne by the Royal Navy.

The new vessel was named Cerberus, after the three-headed hound that guarded the gates of Hades. The choice was deliberate. This was not a ship intended to roam the seas; it was a sentinel, built to deny entry and offer a devastating bite to any would-be intruders.

Cerberus followed the traditional monitor design: heavily armed, armoured, and riding low in the water. In the calm confines of Port Phillip Bay she would present a difficult target, her low profile offering little to aim at while her guns commanded the approaches to Melbourne.

For the voyage to Australia, however, she required significant modification. A temporary iron deck and bulwarks were fitted, along with a full three-masted sailing rig to supplement her engines. Even so, the ship was never intended for open-ocean travel.

The consequences of that decision soon became clear.

A Troubled Voyage

Even before her maiden voyage, Cerberus attracted controversy. Costs overran. Her appointed captain, W. H. Norman, died before taking command. Lieutenant Panter was dispatched from Australia as his replacement, only for the ship’s departure to be delayed by a bureaucratic dispute over whether a vessel of her class could legally sail under the merchant flag.

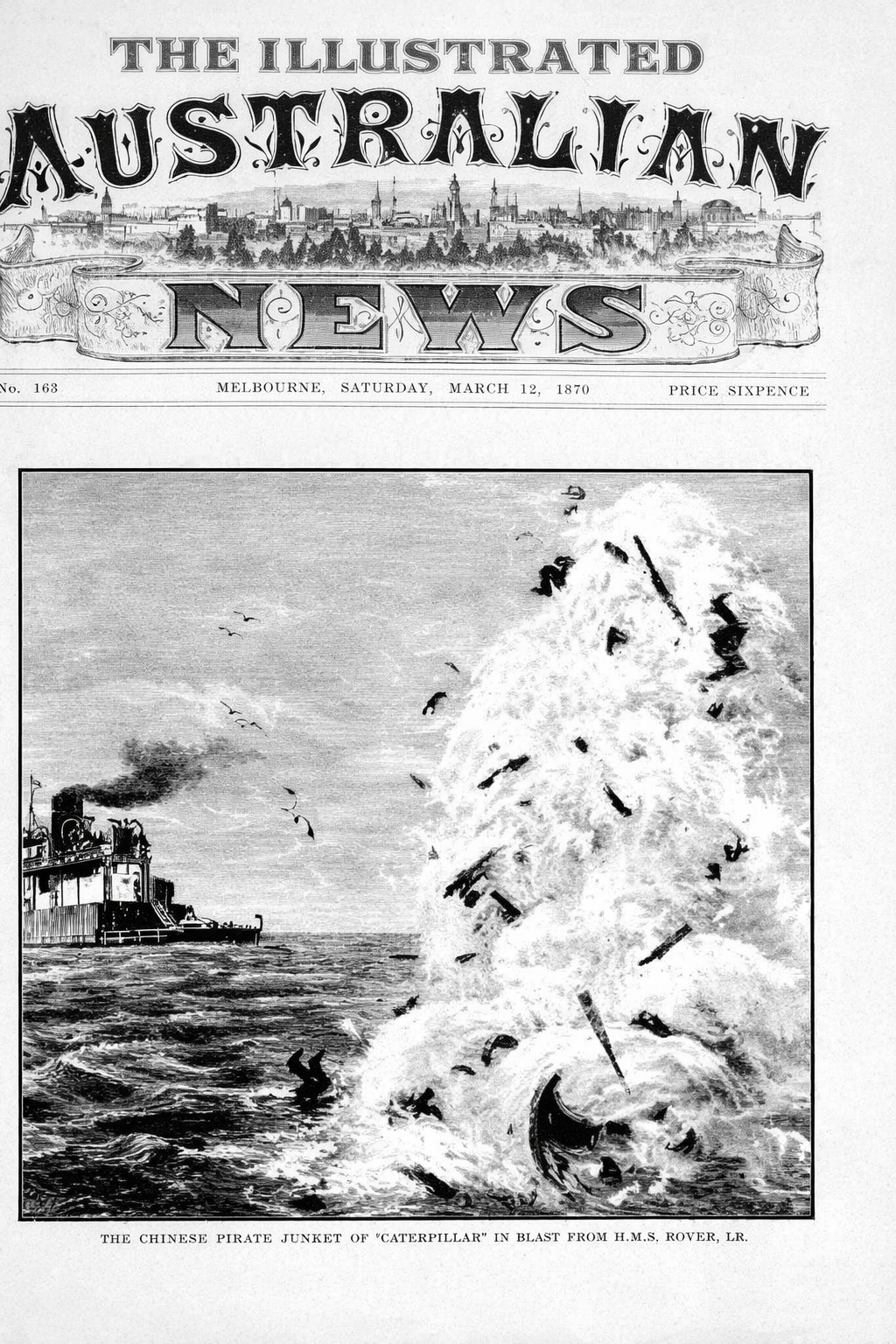

As the Illustrated Australian News reported, a “long and wearisome delay … took place in order to decide under what flag the Cerberus should be sent out, as there was no precedent for a ship of her class being navigated under the merchant flag”. After five months, the matter was resolved and the Admiralty handed the ship over to Lieutenant Panter to prepare for the journey.

It was then discovered that Cerberus carried a six-degree list. Forty tons of shot had been stowed on one side, while only twenty tons of powder occupied the other.

Once underway, matters deteriorated rapidly. En route to Plymouth, the ship encountered a gale during which she proved “perfectly unmanageable”, unable to steer or exceed 1.5 knots under steam. Conditions worsened in the Bay of Biscay. According to The Leader:

“She behaved in a very bad manner, rolling so heavily that on one occasion the bilge pieces were fairly thrown out of the water. The ship rolled quite 45 degrees each way… At this time the only canvas shown was a close-reefed main trysail… Even with this canvas and the steam it was found almost impossible to keep the vessel head to wind.”

By the time Cerberus limped into Gibraltar, her crew was close to mutiny and her coal reserves dangerously low. Under full steam she consumed forty-two tonnes of coal per day; on arrival she had just six tonnes remaining.

Misfortune followed her into the Mediterranean. At Malta, many of the merchant crew deserted en masse. Ten men were imprisoned for insubordination. Only after passing through the Suez Canal did conditions improve, and on 9 April 1871 — a week earlier than anticipated — Cerberus finally entered Port Phillip Bay.

Arrival and Anticlimax

Waiting to greet her were HMS Nelson, whose crew manned the rigging and saluted the new arrival with three cheers, and — by coincidence — the Russian corvette Haydamack, dressed in flags. The display was initially thought to be a gesture toward Cerberus, though it was later explained as a celebration of Easter Sunday, a major holiday in Russia.

Melbourne’s reaction was immediate. As The Leader reported, news of the ironclad’s arrival spread rapidly through the suburbs, prompting a rush to Sandridge. Boatmen did brisk business ferrying sightseers, and before long the decks of the vessel were crowded with curious onlookers.

Yet the spectacle failed to match expectations. Rigged for her voyage, Cerberus looked nothing like the sleek images circulated beforehand. Many were disappointed. As one observer put it, she resembled “an elongated gasometer fitted with masts and yards, and sent to sea on an experimental cruise”.

The disappointment was superficial. Beneath her ungainly appearance lay formidable power.

A Floating Fortress

With a displacement of 3,480 tonnes and a length of 225 feet, Cerberus carried four ten-inch guns — two 18-tonne cannon mounted in rotating turrets — capable of firing both explosive shells and solid shot. She was the first iron-clad monitor to serve in any colonial navy and one of only three of her class ever built.

Designed for defence rather than pursuit, Cerberus was most effective at anchor or moving slowly within confined waters. In that role she was formidable. Today, scuttled at Half Moon Bay, she remains the only surviving example of her class.

Her thirty-year career in the Royal Colonial Victorian Navy was largely uneventful. Active service consisted of trials, drills, and participation in exercises such as the Eastern Manoeuvres. Yet even in routine duty she remained plagued by technical shortcomings.

Her steering gear was notoriously heavy, requiring eight to ten men to turn the wheel. Once altered, her course was equally difficult to correct. As The Argus noted in 1877, it was “impossible to manoeuvre her with any rapidity in the narrow channels of Port Phillip Bay”, a serious limitation for a vessel intended to respond quickly to threats at the Heads.

In 1881, tragedy struck during trials of remote-detonated mines — an emerging technology intended to block shipping lanes. While transferring explosives by rowboat, the oars became entangled in the firing wire. Forty pounds of gunpowder and dynamite detonated instantly, killing four crewmen.

Cerberus was powerful, but she was never comfortable. She embodied both the ambition and the limitations of colonial defence.

Building the Ring of Iron

The defence of Melbourne did not rest on ships alone. Long before the arrival of Nelson and Cerberus, the Victorian military had pressed for permanent shore batteries to protect the Bay.

In 1859, British Army officer Captain Peter Scratchley arrived in Victoria to advise on coastal defences. His recommendations were comprehensive: four gun batteries at the entrance to Port Phillip Bay and an inner ring protecting Hobson’s Bay. Work began the following year on a seawall at Shortlands Bluff, Queenscliff, to support heavy artillery.

The initial garrison consisted of fifty local volunteers — the Queenscliff Company of Volunteer Artillery — under Acting Lieutenant Alexander Robertson. Over the next three years, the first permanent battery was constructed from local sandstone, housing four 68-pound muzzle-loading cannon.

These early works were modest, even as the strategic environment grew more uncertain. Foreign warships visited more frequently. Tensions in Europe ebbed and flowed. British Imperial troops were gradually withdrawn from the colonies, sharpening the need for local self-reliance.

In 1877, the defences received renewed attention through the joint efforts of Scratchley and Lieutenant General Sir William Jervois, Director of Works and Fortifications in London. Their report called for extensive fortification of both sides of the Heads, transforming Queenscliff from a rudimentary battery into a heavily defended stronghold.

Fort Queenscliff and the Heads

At Shortlands Bluff, new walls were erected to guard against landward attack. Garrison numbers increased. Advances in artillery technology were incorporated, most notably in 1888 with the installation of powerful eight-inch “disappearing” guns.

Mounted on hydraulic platforms, these weapons used recoil to drop below ground level after firing, allowing them to be reloaded in safety before rising again. The system protected crews from counter-battery fire and made the guns difficult to target. Each could hurl a 100-kilogram shell over a distance of eight kilometres.

Dry moats surrounded the fort, further complicating any assault. By the late 1880s, a land-based attack on Fort Queenscliff would have been an almost suicidal undertaking.

The defensive network extended beyond the Bluff. Swan Island to the north and South Channel Fort — an artificial island off Sorrento — were fortified with guns, mines and torpedoes to protect shipping lanes. On the opposite side of the Rip, Fort Nepean and the Eagle’s Nest battery completed the ring, with new barracks constructed in 1888.

By 1890, Melbourne was the most heavily defended city in the southern hemisphere.

Deterrence Without War

None of these defences were ever tested in battle. No Russian squadron forced the Heads. No enemy fleet challenged the guns. Yet their presence mattered. They transformed Port Phillip Bay from an inviting target into a formidable obstacle, offering reassurance to a community keenly aware of its isolation.

With Federation, responsibility for Australia’s defence passed to the Commonwealth. Cerberus was transferred to the Royal Australian Navy in 1911 and later served as guard ship during the First World War. Renamed Platypus II, she became a submarine depot ship before being sold and scuttled as a breakwater.

The forts endured longer. Fort Queenscliff and the Point Nepean defences remained operational through both world wars. On 5 August 1914, hours after Britain declared war on Germany, a gun at Fort Nepean fired across the bows of the German freighter Pfalz as it attempted to leave Port Phillip Bay — the first artillery shot fired by the British Empire in the First World War.

It was a brief, bloodless moment. But it confirmed something the Victorians of the 1850s had long believed: that fear, however exaggerated, could reshape a city — and leave it prepared when the moment finally came.